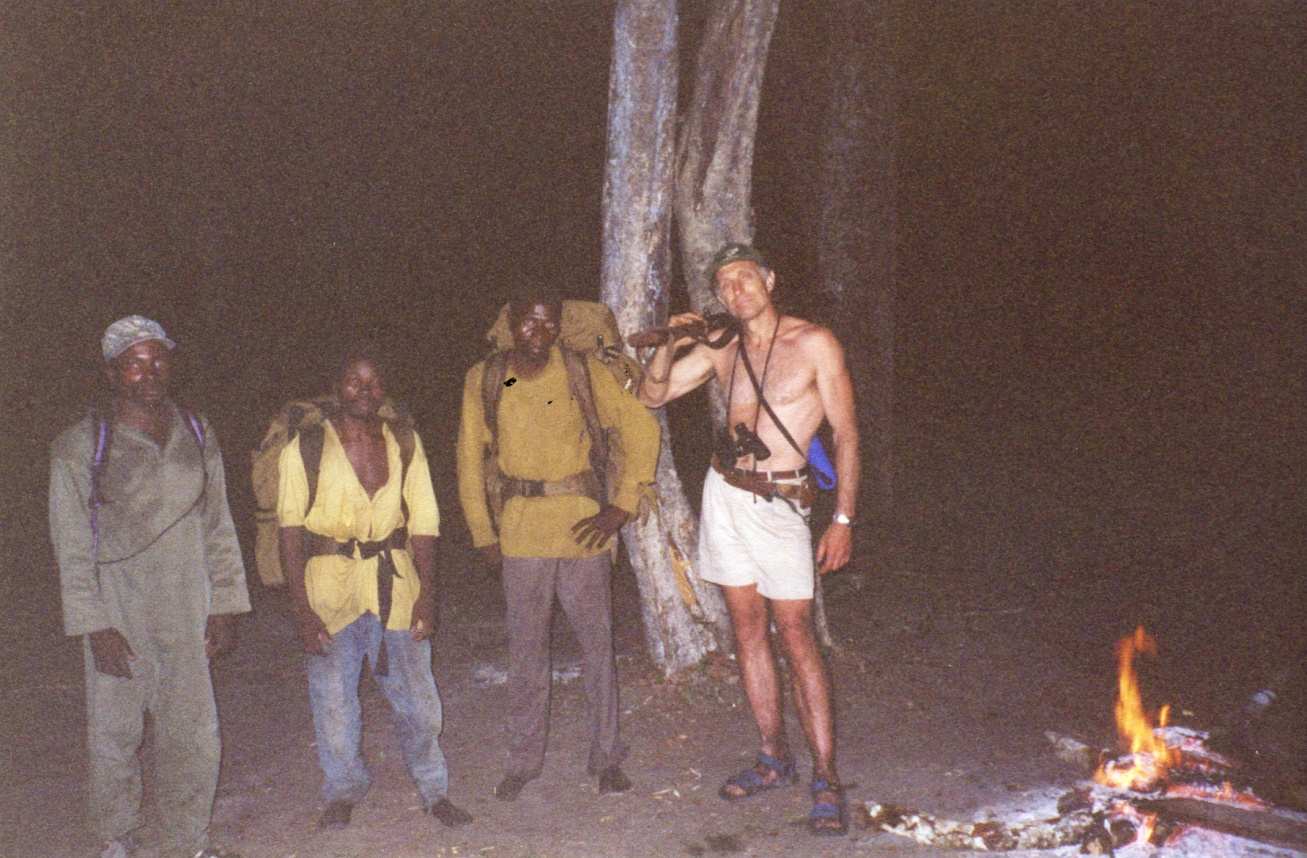

We trudged into fly camp some time after 11pm – Vashtudu, Jantjie, Moosa and me. The pic is Victor’s work. He and Louis were recruited to look after the vehicle; neither was brave enough to stay behind in the bush alone, so I had to take on both.

We found them fast asleep in the cab, their fire abandoned. The hyenas had been giving them hell, they explained, with some embarrassment. Sure enough, the next morning we found the area around was covered in hyena tracks. Vashtudu snorted derisively that they should know better than to leave smelly food left-overs unburied.

We had been on a five-day sojourn to the north-east, then a slow swing more south. We had started angling back on day four. Day five, heading more or less for the vehicle, had been disappointing. It was over flat sand veld, with mostly Wild Syringa and Kiaat forest. The bush was waterless and we saw no animals; not even a sign, apart from some small antelope that live off moisture from vegetation, and pass-through spoor of Eland and Elephant, several weeks old.

By sunset we were about four hours south-east of the vehicle, we reckoned. Vashtudu and I held a quick téte-a-téte. It didn’t seem worthwhile making camp; not for the sake of a four- or five-hour slog in tomorrow’s heat through more lifeless bush, with us already low on water. So, we pressed on in the coolness. The last three hours was in darkness with just a pale halfmoon that slowly shifted down westwards from its zenith.

Actually, I don’t like walking in the dark. It is the time when large predators are most active. Hyenas wouldn’t have been a problem, and a group of four moving together would have seemed a bit daunting to all but the boldest of leopards, but lions… We had heard roaring two nights earlier, but that was now more than sixty kilometres to the south-east. More-over, what would lions do in such prey-less bush, I reasoned, and Vashtudu just nodded.

If you are taking your chances in such unknown stretches of bush, days like that are inevitable. The wilderness has no obligation other than to itself. One is but a fly, a worm, steered by your tracker/guide, mostly on intuition, if he is not familiar with that particular area.

Fashtudu was the tracker/guide/medium. He wasn’t among the greatest bush-men I had worked with, but he had picked up a bit of Fanagolo from working for safari outfitters during the pre-war years, so basic dialogue was possible.

Fanagolo is a kind of pidgin Zulu, developed on the South African mines to enable communication with migrant workers from all over Africa. Zulu as a basis for a lingua franca made sense. Several other Southern African ethnic languages are particularly similar to it, partly because they form part of the Nguni group of languages, but also because the great Chaka Zulu, who ruled over the Zulu nation during the early 1800’s, brought large swaths of territory under Zulu control. Furthermore, like most tyrants, Chaka had many enemies, some of his own people. The Shangaans of southern Mozambique and the Matabele (later situated in the south of Zimbabwe) are large ethnic groups or nations which had their origins closely associated with Shaka’s generals who had defected or refused to accept him as monarch and had moved away to found their own kingdoms.

Anyway, back to our arrival in fly camp.

There wasn’t much – somewhat better food, and more; maybe the bit of red wine left from what I had hauled along over those jarring roads was still drinkable, and that would be a real boon; there would certainly be coffee, but best of all, there was water. Lots of it. I could even heat it in the bucket I had in my bush gear, but I wouldn’t. It was almost midnight and it was still hot and I was tired and I had three days of caked dust and sweat and spider webs and dried blood from thorn cuts and dry plant sap on my body, and it just wanted to be under the luxurious stream of the water and feel it soak in and loosen the dirt; everywhere where the three cups of water of last night couldn’t.

And afterwards there would be sitting in a chair by the fire and sipping at the wine and listening to the African night and not having to think about anything except what floats into the mind, and, finally, that special feel of slipping clean into the sleeping bag.

It would be the ultimate compliment and a real joy if they wold enjoy them.

I enjoyed this one! Just wish it was a bit longer :) Sometimes I wonder where you hide all these tales and pearls of wisdom that I read about on your blog. Some of them I’m familiar with but there are many that I’ve never heard before! Your blog and your books give me so much peace of mind because it’s the only way that your wealth of stories will live on forever. And that’s so valuable. I cannot wait to one day read them to my children :)